Programming in-betweenness through esolangs and codework

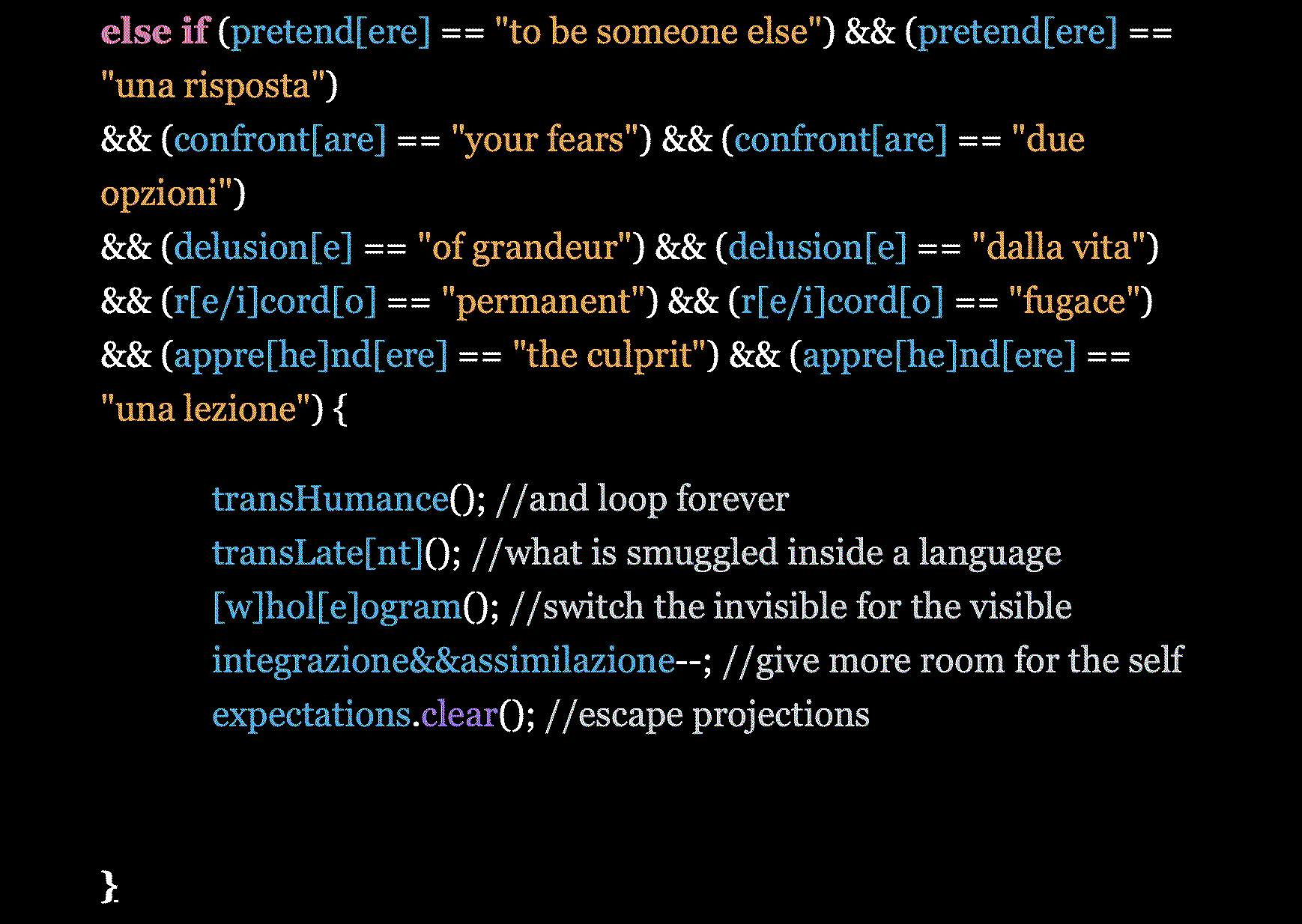

The Electronic Literature Collection Volume 1 defines codework as a “a type of creative writing which in some way references or incorporates formal computer languages (C++, Perl, etc.) within the text. The text itself is not necessarily code that will compile or run, though some have added that requirement as a form of constraint” (2006). One of the first examples of codework is Mezangelle, an online language developed in the early ‘90s by Australian-based artist Mez Breeze. Combining conventions from formal programming languages with colloquial speech, Mezangelle positions itself as a non-executable code emulation experiment with a social commentary function (Dean, 2016). Through the use of square brackets to indicate all the possible readings of a word, Breeze creates a language that escapes one singular interpretation and the right/wrong dichotomy.

One of the main aims of the language, as seen by Breeze, is to challenge the type of exclusionary culture that might develop as a result of binary systems (Dean, 2016). This is achieved through a rejection of Boolean expressions in favour of trinary logic and the use of “semantic triggers combined with an individual's own subjective meaning framework” (Dean, 2016). Some readers of Mezangelle might try to execute the code, but making it computer-parsable means removing any ambiguity from it and reducing all levels of interpretations to one. The freedom granted by non-executable codework consists in taking advantage of the structure of code to shed light on the structural elements of computational technology while not being bound by its rules (Risam, 2015). By relying on the reader’s own interpretation, based on their personal set of interests, beliefs and lived experience, Breeze opens up possibilities for what a programming language could be, while revealing the rules that constrain formal programming languages.

Another creative project aimed at challenging “the structure, logic, and semantic meaning at the basis of constructing computer code” (Blas, 2008a) is Zach Blas’ transCoder. Part of Blas’ Queer Technologies project (2008-12), transCoder: Queer Programming Anti-Language is designed as an unfinished open-source software development kit meant to be collectively built (Gaboury, 2010). Its goal is not just to uncover the systems of oppression intrinsic to mainstream technology, but to offer alternatives based on queer theory. In “an attempt to severe ontological and epistemological ties to dominant technologies and interrupt the flow of circulation between heteronormative culture, coding, and visual interface” (Blas, 2008b), transCoder comes with its own code libraries, modelled on critical theory texts by scholars such as Michel Foucault, Donna Haraway and Jack Halberstam. Besides offering alternative coding structures, the transCoder manifests the idea of a queer anti-language in its centring movement and morphing; in its rejection of Boolean true/false statements for a multitude of co-existing states; if/then logic fading into a series of infinite if/if/if possibilities; the whole language in a constant state of fluctuation and unpredictability. This ambiguous and experimental quality allows for open-ended use of the transCoder, including poetic applications.

In her book Poetic Operations (2022), micha cárdenas shares a poem she wrote using the transCoder software development kit combined with the code for the Transborder Immigrant Tool (Rhizome, 2019). Using codework to convey shifting states of identity and being, she draws a link between the experience of immigrants crossing the Mexican border into the US to the experience of trans people. Mirroring the working of functioning programs, she starts by declaring a list of variables constituting the elements that make an identity, and then adding in the operations that describe how the different parts interact. Reducing algorithms to their core components - a list of parts and operations defining the relationships between the parts - she regards them as a way to understand complex systems of oppression and identity (cárdenas, 2022, p. 9).

Furthermore, cárdenas explains how words can be read as algorithms, as in words such as “Latinx”, and “trans*” where the “x” and the asterisk can work as variables or placeholders, indicating expansions and future possibilities (cárdenas, 2022, p. 11). This “indeterminate, poetic application” (cárdenas, 2022, p. 8) of algorithms also supports multiple levels of meaning, in a similar way to how Mezangelle allows for multiple interpretations. Her work focuses on movements, gestures and operations, which is reflected in the ritualistic and performative quality of her codework. The code poem in Poetic Operations is meant to be read out loud and acquires meaning through repetition, such as in the initial declaration of variables, which are themselves “performative in that they exist only at run time” (cárdenas, 2022, p. 148).

The performative and time-based aspects of code are also explored in esolangs (esoteric programming languages) centred around oral storytelling traditions, such as Jon Corbett’s Cree#. Similarly to codework, esolangs represent an alternative way to write code that doesn’t prioritise productivity and usability, but pushes the boundaries of what a programming language can be (Morr, 2015). Part of his Indigenous Coding Framework and Indigenous Digital Media Toolkit, Cree# centres the cultural perspective of people of the Cree nation, with an output that is both generative and graphical (Corbett, no date). The programming language utilises the Indigenous language’s orthography and the generative aspect that Corbett describes as intrinsic of Indigenous worldview: when the program ends whatever was generated is destroyed, mimicking the workings of oral storytelling (Temkin, no date).

In-betwenness in multilingual experiences and translation

Translation, moving physically and linguistically between countries, assuming different identities when speaking different languages and states of linguistic in-betweenness are all themes widely discussed in literature beyond computational theory and programming languages. For this project, I decided to refer to memoirs by three women writers; Polly Barton’s Fifty Sounds (2021) and Mireille Gansel’s Translation as Transhumance (2017), both of which focus on translation and Ágota Kristóf’s L’Analfabeta (2005), which explores the experience of re-learning how to express oneself in a foreign language. While the experiences portrayed within these texts are varied and both similar and different from my own, I chose to include references to particular sections of these texts in my code library due to the fluency with which they described experiences of displacement and translation.